More Sonos: How a Two-Part Patent Figure Led to a $32.5M Reversal

A specification disagreement between N.D. Cal. and the CAFC

The Federal Circuit’s decision to reinstate Sonos’s $32.5 million jury verdict against Google hinged on a fundamental disagreement with the district court over a few key lines in a patent application filed in 2007. Judge William H. Alsup, in his October 2023 post-trial opinion, concluded that Sonos’s original patent filings failed to describe the claimed "overlapping zone scene" invention, leading him to invalidate the patents. The Federal Circuit panel, however, looked at the exact same patent text (and figures) and found the opposite, concluding the disclosure was clear since at least 2013. This stark difference in interpretation of the patent specification proved to be the decisive factor in the entire case.

Judge Alsup: “Sleight of Hand”

Judge Alsup’s post-trial analysis was built on the premise that Sonos’s early patent applications were devoid of any real disclosure for the key overlapping feature. He argued that Sonos only created support for its claims in 2019 through an improper amendment, which he deemed “new matter” and a “sleight of hand” (Post-Trial Decision, p. 55).

In his view, Sonos took a description of a feature for ad-hoc, real-time grouping (“Zone Linking”) and deceptively reappropriated it to describe the setup of pre-set, saved groups (“Zone Scenes”). He believed the original specification provided only a "forest" of general ideas, and to find the specific claimed invention was like looking for "blaze marks which single out particular trees" where there were none (Post-Trial Decision, pp. 52-53).

In his scathing critique, Judge Alsup asserted that Sonos’s disclosure was so deficient that one could not find the novel aspects of the invention without resorting to improper inference, stating, “novel aspects of the invention must be disclosed and not left to inference” (Post-Trial Decision, p. 52).

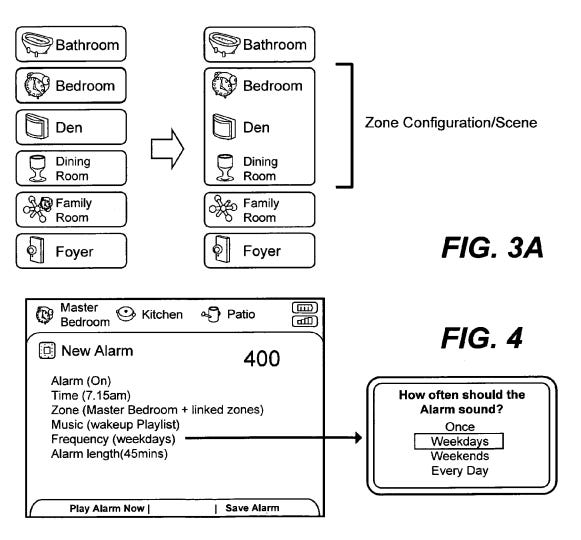

He further contended that Sonos’s mixing and matching of perceivably different embodiments in its arguments did not constitute a valid disclosure, as a claimed invention is not supported "by picking and choosing claim elements from different embodiments that are never linked together in the specification" (Post-Trial Decision, p. 42 (quoting Flash-Control, LLC v. Intel Corp.). For Judge Alsup, the original document was fatally ambiguous, including FIGS. 3A and 3B of the patents at issue, and Sonos’s subsequent actions to clarify it were deceptive, rendering the patents invalid.

The Federal Circuit: A “Plainly” Adequate Description from 2007

The Federal Circuit panel saw the situation entirely differently. It bypassed the controversy around the 2019 amendment by finding the original 2007 non-provisional application already contained a sufficient written description (U.S. Pat. No. 8,483,853).

The CAFC found its proof in the specification’s description of a “Morning Scene” and an “Evening Scene.” The panel noted that the disclosure described the Morning Scene as containing the “Bedroom, Den and Dining Room” and the Evening Scene as also containing “those same rooms, in addition to the Garage and Garden” (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 13).

This, the court concluded, “plainly provides adequate written description for overlapping zone scenes, where each of the Bedroom, Den, and Dining Room simultaneously belong to two different zone scenes” (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 13).

The Federal Circuit directly rejected the argument—embraced by Google and Judge Alsup—that these were merely “alternative embodiments” that were not described as coexisting. The panel found this interpretation unreasonable, stating, "Figures 3A and 3B are complimentary, not alternative" (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 14).

The CAFC opinion pointed to the specification’s own language, which introduces the second figure by stating, "[e]xpanding this idea further, a Zone Scene can be set to create multiple sets of linked zones" (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 13). Based on this explicit textual bridge, the panel concluded that "[n]o reasonable factfinder could conclude" that the specification was describing separate, unrelated embodiments (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 14).

Just the Facts

While the Federal Circuit corrected the district court's legal framework from a 35 U.S.C. § 102 anticipation analysis to a § 112 written description analysis, the panel explicitly characterized this as a likely "distinction without a difference" (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 10). Looking at the disclosure through the legal lens of § 112 did not matter.

Both legal pathways hinged on the same dispositive question: whether the original 2007 application provided adequate support for the claimed invention. Answering this question in the negative would have invalidated the patents under either statute by shifting the priority date.

Interestingly, the standard of review for the written description issue was different from review of the alleged evidence of any prejudice (prosecution laches). The Federal Circuit treated the written description part of the decision as a review of summary judgment, which is always reviewed de novo (e.g., no deference to the lower court) (Fed. Cir. Op., p. 12).

Because the Federal Circuit answered the core question in the affirmative, the patents were deemed validly supported from their original filing, making the specific statutory lens for the analysis immaterial to the final judgment.

The Decisive Interpretive Divide

This direct conflict over the meaning of the specification is the key to understanding the case's dramatic reversal.

Judge Alsup saw two disconnected examples and concluded that any link between them was an improper, after-the-fact invention by Sonos’s lawyers (and expert).

The Federal Circuit, however, saw the specification’s own words—"[e]xpanding this idea further"—as an explicit instruction to read the two examples together as a cohesive, evolving disclosure.

What one judge viewed as a fatal ambiguity requiring an improper amendment, the appellate panel viewed as a plain and adequate description present from the outset.

When drafting patent specifications and figures, multiple examples of various embodiments can carry the day.

This single point of interpretive difference likely was the legal fulcrum on which the entire case turned, leading directly to the reversal of invalidity and the reinstatement of the $32.5 million verdict. It turns out that patent pictures can be worth well more than a thousand words.

Disclaimer: This is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or financial advice. To the extent there are any opinions in this article, they are the author’s alone and do not represent the beliefs of his firm or clients. The strategies expressed are purely speculation based on publicly available information. The information expressed is subject to change at any time and should be checked for completeness, accuracy and current applicability. For advice, consult a suitably licensed attorney and/or patent professional.