Federal Circuit Affirms Ineligibility of Map Locator Patents, Citing Conventional Tech and Functional Claims

Cascades' limitations were found "indisputably conventional as of 2007"

In a non-precedential decision that reinforces the high bar for software patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has affirmed the invalidation of several patents related to a mobile brand-locating application. The court’s analysis sends a critical message to inventors and patent practitioners: while relying on functional outcomes is already a risky claiming strategy, admitting in the specification that the underlying components are conventional digs a hole for the patent so deep that it creates an almost inescapable eligibility challenge.

The decision in Cascades Branding Innovation LLC v. Aldi, Inc., No. 2024-1729 (Fed. Cir., Sept. 25, 2025), provides yet another example of how courts apply the Alice framework to dismiss patent infringement suits at the earliest stages of litigation. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the patent claims were directed to the abstract idea of finding and displaying business locations on a map and lacked any inventive concept to render them patent-eligible.

Background of the Dispute

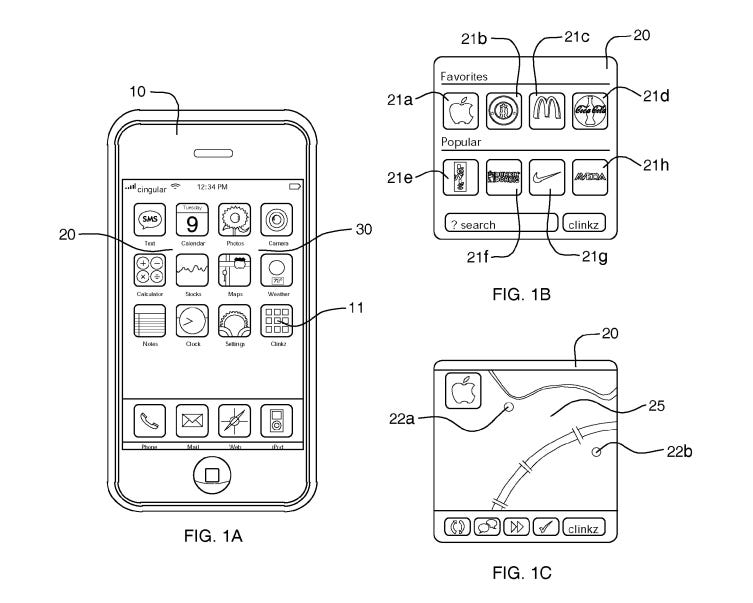

Cascades Branding Innovation LLC (”Cascades”) sued Aldi, Inc. (”Aldi”), alleging that Aldi’s proprietary mobile application infringed three of its patents: U.S. Patent Nos. 7,768,395; 8,106,766; and 8,405,504. The patents, all filed in June 2007, describe a method for helping a user find nearby locations associated with a particular brand.

The court treated claim 1 of the ‘395 patent as representative of all asserted claims. It recites:

A method comprising:

(A) displaying, using a device, a first image associated with a first brand;

(B) receiving, from a user of the device, an indication of a selection by the user of the first image;

(C) identifying a first location of the device independently of any location-specifying input provided by the user to the device;

(D) identifying a first brand access site at which a first branded entity having the first brand is accessible; and

(E) providing to the user, using the device, a first map image which describes a first geographic area derived from the first location of the device and which includes a first indication of the first brand access site.

Cascades alleged that Aldi’s app, which allows users to tap the Aldi logo to see nearby supermarket locations on a map based on their phone’s GPS data, practiced this patented method.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois granted Aldi’s motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), finding all asserted claims invalid under § 101 (Slip Op., p. 2).

Concluding that no amendment to the complaint could cure the fundamental eligibility defect, the district court dismissed the case “with prejudice” (p. 4). Cascades appealed this final decision to the Federal Circuit.

The Court’s Analysis: Unpacking the Central Legal Issue

The central legal issue before the Federal Circuit was whether the district court erred in finding the patent claims directed to a patent-ineligible abstract idea under the two-step framework established in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208 (2014).

At Alice step one, the district court had determined the claims were “directed at the abstract idea of collecting geographic information about the location of a device and nearby stores or businesses offering certain products, and displaying that information to the user” (p. 3). Cascades argued this characterization was too broad.

The Federal Circuit, however, found “no error in the district court’s characterization or its determination that the claims are directed to an abstract idea” (p. 5). The panel held that the claims were articulated in purely functional terms, focusing on the desired result rather than a specific technical solution. The panel quoted the district court’s rationale with approval:

“[The claims] merely use functional language to describe the desired result, without any technological details about how that result is implemented or that improves on existing computer technology” (p. 3).

The Federal Circuit emphasized its precedent that “claims directed to nothing more than collecting, analyzing, and displaying information, even when limited to a particular field of endeavor, [are] abstract” (p. 6, citing Elec. Pwr. Grp., LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350, 1353–54 (Fed. Cir. 2016)).

For Alice step two, Cascades argued its method improved on prior art by allowing a user to locate a business more quickly. The panel rejected this, concluding that the claim elements were all performed using generic and conventional computer technology. Any purported speed advantage “comes from the conventional computer technology itself rather than any inventive step” (p. 8).

The court further explained that “merely adding computer functionality to increase the speed or efficiency of the process does not confer patent eligibility on an otherwise abstract idea” (p. 8).

Conventional Wisdom?

The Cascades opinion is an example of how a court’s initial perspective on “conventionality” can shape its entire patent eligibility analysis, leading to a seemingly inevitable conclusion of invalidity.

The Federal Circuit’s analysis in Cascades essentially began by establishing that every piece of the claimed invention was already well-known, generic, and/or ordinary. The court immediately dissected the claim into its parts—a touch screen, GPS location services, and a map display—and labeled them all as conventional technology as of the 2007 filing date (p. 8). The court found its strongest evidence for this in the patent’s own specification (p. 7).

A case can be made that the claim is directed to a specific improvement in mobile device functionality—a streamlined, single-action user interface that solves the problem of efficiently connecting a user to nearby brand locations. For whatever reason, the terms UI, GUI, or “interface” do not appear in the CAFC opinion.

At step two, the panel dismissed the primary benefit of the invention—a faster and easier user experience—by attributing the speed advantage to the “conventional computer technology itself rather than any inventive step” (p. 8).

One might say that the court did not see a novel arrangement of the parts as the invention because its focus was too fixed on the apparent ordinary nature of the individual pieces. However, the claim’s lack of specificity and its heavy reliance on functional language did not do it any favors, either.

Key Takeaways and Practical Implications

The Cascades decision offers several critical lessons for patent drafters and litigators navigating § 101.

The Specification Can Be Your Undoing. The court repeatedly used Cascades’ own specification against it to confirm the conventionality of the claimed steps. The opinion notes the patents themselves state that “generic and pre-existing computer functionality can perform all the claimed steps” (p. 7) and declares that the “conventionality of the various components was well-established by the specification itself” (p. 8). This highlights the danger of admitting in the patent disclosure that the invention can be implemented entirely with “off-the-shelf” components.

Admission of Conventionality is a Deep Hole: In a § 101 analysis, a few words from the patent’s own specification can set the tone for the entire proceeding. The admission here was fatal, directly leading the court to affirm the dismissal with prejudice. The panel reasoned that because the patent itself confirmed the building blocks were generic, no amendment could save the claims. As the court concluded, “No amount of new allegations or additional evidence could change that reality or the patent’s specification” (p. 9). This takeaway is stark: admitting components are conventional is not just a weakness, it likely makes the step-two hill even steeper.

Functional Claiming Without Technical Detail is a Losing Strategy. The court’s analysis reinforces the well-established principle that claiming a result without teaching how to achieve it in a novel way is a hallmark of an abstract idea. The claims here were described as being written in “highly generic functional terms” (p. 3) that failed to provide “any technological details about how these steps are to be implemented” (p. 3). For practitioners, the message is clear: patent claims must be grounded in a specific, technical implementation. Focusing on the “what” (e.g., displaying a map with brand locations) at the expense of an inventive “how” (e.g., a new algorithm for processing location data) likely leaves a patent acutely vulnerable to a § 101 challenge.

An “Improvement” Over Prior Art Must Be Genuinely Technical. Cascades attempted to frame its invention as a technical solution to a problem by comparing its icon-based selection method to prior art text-based search methods. However, the court found that “the claims do not describe any technological details about how that result is implemented” (pp. 5-6). The panel held that the benefit of clicking an icon—speed—was an inherent advantage of using the conventional computer technology, not the invention (pp. 7-8). This serves as a caution: simply identifying a problem in the prior art and claiming a more efficient, user-friendly method is insufficient. The claimed solution must itself represent a technological improvement over what was previously known, not just a more logical application of existing technology.

Conclusion

The Federal Circuit’s decision in Cascades v. Aldi does not break new legal ground but rather provides a firm and example of applying the established § 101 precedent.

It reaffirms that the CAFC intends to protect specific technological solutions, not abstract ideas implemented with generic tools.

For those seeking to patent software-based inventions, the message is clear: the focus must be on an inventive technological core. Simply claiming a better result on a standard computer is not enough to secure a valid patent. As technology continues to advance, the line between an abstract idea and a patent-eligible application will remain a central and contested feature of patent law.

Disclaimer: This is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or financial advice. To the extent there are any opinions in this article, they are the author’s alone and do not represent the beliefs of his firm or clients. The strategies expressed are purely speculation based on publicly available information. The information expressed is subject to change at any time and should be checked for completeness, accuracy and current applicability. For advice, consult a suitably licensed attorney and/or patent professional.