Desjardins Shift: PTAB Invokes Memo & Reverses 101-Rejection in

Ex Parte Wu Uses Squires §101 Analysis

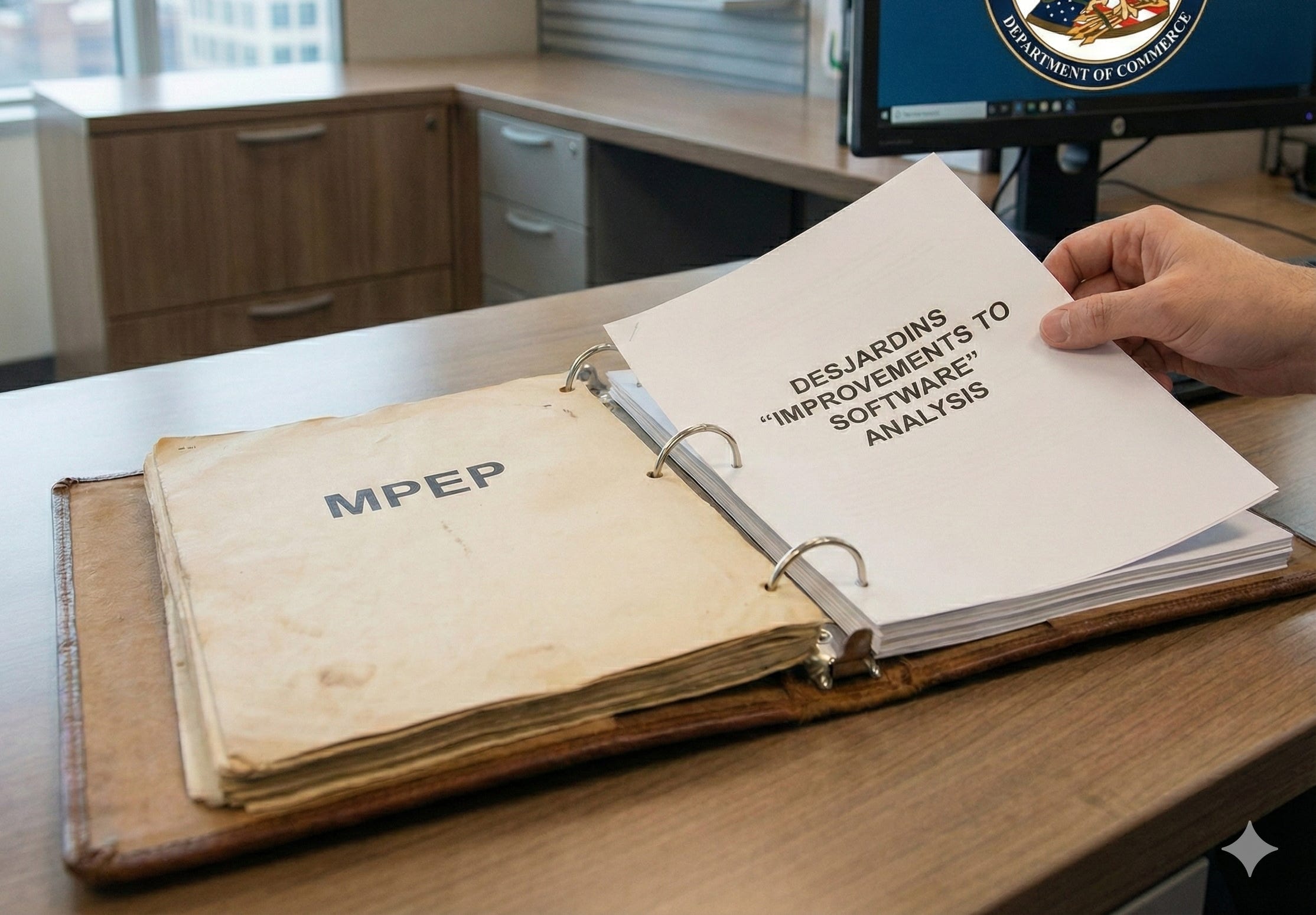

The intersection of artificial intelligence and biotechnology continues to generate some of the most complex patent eligibility disputes at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). For years, applicants claiming software and AI-based simulations faced an uphill battle against Section 101 rejections, often trapped by the “abstract idea” exception. However, the legal environment shifted significantly in December 2025 with the designation of Ex Parte Desjardins as precedential and the subsequent updates to the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP). Watching how the USPTO applies these principles in examination and appeals will be vital.

A recent (nonprecedential) decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), Ex parte Lingfei Wu et al., Appeal 2025-002027 (PTAB Dec. 19, 2025), offers a new example of how this new guidance is reshaping prosecution for computational biology.

In a decision mailed December 19, 2025, the Board reversed a Section 101 rejection against an IBM and MIT joint application, finding that an AI model for simulating protein structures was patent-eligible. The PTAB opinion cited Desjardins and the new memo significantly.

Background of the Dispute

The technology at issue (Appl. No. 16/585,679) addresses a fundamental challenge in bioengineering and materials science: predicting the three-dimensional structure of proteins. The application, filed jointly by International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), describes a method for “3D structure analytics of raw amino acid protein sequence” (p. 2, quoting Spec. ¶ 22).

Traditional methods for determining how a protein folds often rely on “classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations or experimental verification,” which the Specification notes are “unable to generalize well to a new sequence design” (p. 11, quoting Spec. ¶ 24).

The inventors proposed a solution utilizing a “multi-scale neighborhood-based neural network (MNNN)” (p. 2). This deep learning model predicts dihedral angles—the angles between planes of atoms—directly from raw amino acid sequences. These predictions are then used to simulate the final protein structure.

The Examiner rejected claims 1-25 under 35 U.S.C. § 101, asserting they were directed to patent-ineligible abstract ideas. Specifically, the Examiner categorized the neural network computations as “mathematical concepts” and the simulation steps as “mental processes” (p. 6).

The Examiner further argued that the claims lacked an inventive concept, characterizing the additional elements as “mere gathering and analyzing information” that did not integrate the abstract idea into a practical application (p. 7).

The Board’s Analysis: Unpacking the Central Legal Issue

The central legal issue was whether the claims, which undeniably rely on mathematical algorithms and computational modeling, were “directed to” an abstract idea or whether they were integrated into a practical application under Step 2A, Prong Two of the Alice framework.

The Board’s analysis reflects the recent doctrinal adjustments following Ex parte Desjardins. The Board acknowledged the USPTO’s revised guidance:

On September 26, 2025, an Appeals Review Panel issued a decision in Ex Parte Desjardins... analyzing eligibility in terms of whether a claim is directed to an improvement in the functioning of a computer, or an improvement to other technology or technical field… On December 5, 2025, the Office issued a Memorandum, Advance notice of change to the MPEP in light of Ex Parte Desjardins, revising the MPEP to include Ex Parte Desjardins (p. 5).

Step 2A, Prong One: Mathematical Concepts, Not Mental Processes

The Board agreed with the Examiner on one point: the limitation reciting “computing one or more amino acid character embeddings... by utilizing a multi-scale neighborhood-based neural network” recited a mathematical concept. The Board noted that neural networks comprise “computer algorithm[s] that perform[] mathematical computations to organize data through mathematical correlations” (p. 9).

However, the Board firmly rejected the Examiner’s assertion that the step of “simulating a protein structure based on the predicted one or more dihedral angles” constituted a mental process (p. 9). The Examiner argued this step could be performed in the human mind.

The Board disagreed, citing the Appellant’s argument that “the human mind is not equipped to perform the claim limitations” required for 3D structure analytics via a multi-scale AI model (p. 10).

This distinction—based in case law cited in MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2)(III)—is vital for software and AI practitioners: complex computational outputs are not mental processes simply because a human can think about the result.

Step 2A, Prong Two: Integration via Technological Improvement

The decisive victory for the Appellants came in the integration analysis. The Examiner had argued that the process merely produced “new information” (e.g., dihedral angles) without a “practical application in the real-world realm of physical things” (p. 10).

The Board reversed this finding, clarifying that “mere physicality or tangibility of an additional element or elements is not a relevant consideration in Step 2A Prong Two” (p. 10-11).

Drawing on Desjardins and Federal Circuit precedent like McRO (p. 11), the PTAB focused on whether the method improved the specific technology of protein design.

The Board found that the claims did more than calculate numbers; they solved a specific technical problem. The decision highlights that the method “predict[s] dihedral angles without (i.e., in the absence of) any template, structural biological knowledge, or co-evolutional information” (p. 12).

By removing reliance on ad-hoc molecular dynamics (MD) simulations or templates, the claims offered a specific improvement to the field (p. 11, quoting Spec. ¶ 24).

The Board concluded:

Thus, we agree with Appellant that claim 1 is directed to a specific improvement to the technical field of protein design, simulation, and synthesis as used in ‘bioengineering, medicine and materials science’ applications (pp. 12-13).

Key Takeaways and Practical Implications

The Ex parte Wu decision, read in conjunction with the Desjardins guidance, provides a clearer roadmap for patenting simulation and AI technologies in 2025 and beyond.

1. The “Improvement” Argument is Paramount The Desjardins precedent has solidified the “improvement to technology” pathway as the primary mechanism for overcoming Section 101 rejections in the AI space (via Enfish). The Board did not require a physical machine or a tangible transformation. Instead, it looked for a specific enhancement over prior methods—in this case, the ability to predict folding without templates. Practitioners should frame specification drafting and response arguments around specific technical limitations of prior approaches (e.g., inability to generalize, reliance on templates) that the new AI model overcomes.

2. Simulation Results Are Valid Practical Applications This decision reinforces that “simulating” a physical system can be considered a practical application, provided the simulation reflects a technological improvement. The Examiner’s attempt to dismiss the output as mere “data analysis” failed because the simulation was tied to a specific domain (protein structures) and solved a domain-specific problem. Patent attorneys should aggressively push back against “extra-solution activity” rejections when the “data” represents a complex physical structure.

3. “Mental Process” Rejections Have Limits The Board’s dismissal of the mental process rejection is a helpful citation for AI cases. When a claim involves “computing embeddings” or “utilizing a neural network,” practitioners should argue that the complexity and volume of calculations render the process practically impossible for the human mind, thereby removing it from the mental process category. This may not be the decisive factor for eligibility, but it could be persuasive with other arguments.

Conclusion

Ex parte Wu stands as an example in the evolving nature of patent eligibility at the USPTO. Following the guidance stemming from Desjardins, the Board effectively dismantled the notion that software simulations are inherently abstract or that “tangibility” is a prerequisite for patentability.

For the bioengineering and AI communities, this decision confirms that methods improving the process of discovery—even if that process occurs entirely in silicon—can be deserving of patent protection. Tying algorithmic innovations to concrete technical improvements remains the most reliable strategy for demonstrating eligibility.

While agency policy and leadership can change (and has), Enfish and other positive precedent still stand as the guide on Section 101. The USPTO’s “practical application” test is approaching its 7-year anniversary, but it is still not endorsed by the Federal Circuit.

The timing of the reversal feels a bit unfair for the examiner, as the final rejection was in May 2024 and the briefing finished in April 2025. Applicants and practitioners who appealed eligibility decisions back then—before Desjardins was a twinkle in Director Squires’ eye—should consider themselves lucky.

Based on the announcements, memos, and (hopefully) training, the USPTO examining corps seems to be adopting the so-called Squires-101 approach; however, with other distractions, the difficult change in course direction may take a while.

Disclaimer: This is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or financial advice. To the extent there are any opinions in this article, they are the author’s alone and do not represent the beliefs of his firm or clients. The strategies expressed are purely speculation based on publicly available information. The information expressed is subject to change at any time and should be checked for completeness, accuracy and current applicability. For advice, consult a suitably licensed attorney and/or patent professional.