Crusoe Not Lost: USPTO Highlights April DRP Reversal of § 101 Ineligibility Finding

Burdens in Challenging Subject Matter Eligibility

In an April 2025 opinion on patent eligibility, recently highlighted by the USPTO in a November webinar, a Delegated Rehearing Panel (DRP) of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has vacated a finding of subject matter ineligibility in Crusoe Energy Systems, LLC v. Upstream Data Inc. (PGR2023-00039). The decision underscores the critical distinction between claims directed to an abstract result and those directed to a physical machine composed of tangible components.

While the outcome offers a degree of relief for those operating at the intersection of energy and blockchain technology, practitioners should observe the specific factual underpinnings of this reversal with a measure of caution.

Still, it was spotlighted in the USPTO Hour webinar, so it’s worth taking note. The opinion’s distinction, between claims that merely involve an abstract idea and those that actually recite one, highlights that claims describing a machine and its constituent parts may be eligible (even if they relate to a general concept).

The Procedural Posture

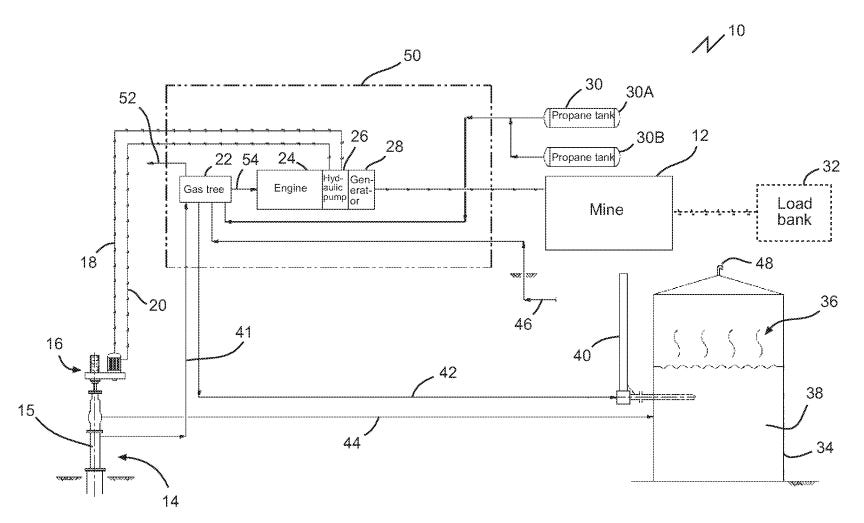

The dispute centered on U.S. Patent No. 11,574,372, which describes systems for using combustible gas—often flared waste gas from hydrocarbon facilities—to power blockchain mining operations.

The procedural history reveals a sharp divergence in how the claims were viewed. The initial Board panel found independent claim 1 ineligible, viewing it as “directed to the abstract idea of ‘using natural gas to power a blockchain mine’” (p. 5). Under this view, the claim was seen as leveraging a fundamental economic practice using generic components.

However, upon sua sponte Director Review, the DRP reversed this determination. The panel concluded that the Petitioner had “not met its burden to show... the claims were ineligible” (p. 2). The panel consisted of Deputy Chief Administrative Patent Judge Jacqueline Wright Bonilla and Vice Chief Administrative Patent Judges Michael P. Tierney and Michael W. Kim.

The DRP’s reasoning turned on the structural nature of the claims. Unlike the initial panel, the DRP determined that “Claim 1 does not describe a result or effect that itself is an abstract idea. It describes a machine defined by its constituent parts” (p. 11). The case was appealed to the Federal Circuit, but recently settled and dismissed.

Deconstructing the “Abstract Idea” Argument

The Petitioner argued that the patent “centers around the abstract idea of using natural gas to power a blockchain mine” and that the physical limitations—such as generators and mining processors—were merely generic machinery used to achieve that abstract result (p. 10).

The Petitioner relied heavily on Yu v. Apple Inc., where claims directed to using multiple cameras to enhance images were found ineligible because they were directed to the abstract result of image enhancement itself.

The DRP rejected this analogy. The panel noted that Yu involved claims explicitly recited as “producing a resultant digital image,” effectively claiming the result itself. In contrast, the DRP found “nothing similar to Yu recited in claim 1” (p. 12).

Instead, the DRP focused on the specific language of the claims. They noted the claim described “seven interconnected elements that together form an integrated system for mining transactions,” including:

A source of combustible gas;

A generator connected to that source; and

Blockchain mining devices with specific network interfaces (p. 10).

The panel reasoned that while the specification discussed the economic advantages of using waste gas, those advantages did not transform the physical system claims into an abstract idea. As the opinion states, “The words of the claim itself indicate otherwise” (p. 12).

Consequently, the DRP did not even need to reach Step 2A, Prong Two (integration into a practical application) or Step 2B (inventive concept), finding the inquiry ended at Prong One (p. 13).

USPTO Webinar Highlighted: Burden of Proof

During a recent discussion on patent eligibility, the USPTO pointed to Crusoe as a pivotal example of the rigorous burden placed on petitioners in post-grant proceedings.

The webinar emphasized that the DRP vacated the Final Written Decision’s eligibility determination precisely because the burden of proof had not been satisfied (slide 28; video, 36:17).

As the DRP explicitly concluded, the “Petitioner has not met its burden of showing, by a preponderance of the evidence, that claims 1 and 24 are patent ineligible” (p. 13).

The panel reasoned that the challenger failed to identify how the specific language of the claims recited an abstract idea, noting that “Claim 1 does not describe a result or effect that itself is an abstract idea. It describes a machine defined by its constituent parts” (p. 11).

This focus on the “constituent parts” suggests that the USPTO is keenly focused on whether a challenger has sufficiently mapped the alleged abstract idea to the actual claim limitations, rather than merely summarizing the invention’s economic purpose.

Analysis: Benefits, Challenges, and Risks

Before integrating this decision into broader prosecution or litigation strategies, stakeholders should weigh the following factors.

Benefits

Clarity for Hardware Systems: The decision reinforces that claims reciting specific, interconnected hardware components (”constituent parts”) are less likely to be categorized as abstract ideas, even if they achieve an economically useful result.

Burden of Proof: The DRP emphasized that the burden lies strictly with the Petitioner. Merely summarizing a claim into a high-level purpose (e.g., “using gas to mine crypto”) is insufficient if the claim language recites a defined machine (p. 10).

Encouragement for Infrastructure Innovation: Technologies that repurpose energy waste for computing power may find a friendlier reception at the PTAB, provided the claims focus on the physical architecture rather than the business method.

Challenges

Drafting Precision: The distinction between a “result” and a “machine” can be subtle. Practitioners must ensure claims are structured as physical systems with defined interconnections, rather than functional steps leading to a desired outcome.

Distinguishing Yu: The Yu precedent remains a potent weapon for challengers. Overcoming it requires demonstrating that the claim is not merely “directed to a result or effect” but is defined by how the components are arranged.

Risks

Fact-Specific Nature: This holding is highly specific to the “machine” nature of the claims. Purely software-based blockchain innovations may not benefit from this reasoning if they lack, e.g., the “source,” “generator,” and “device” physical structure present here.

Future Reversals: While the DRP vacated the § 101 findings, the obviousness challenges in the case remain relevant. A patent eligible under § 101 may still fall under § 103, and reliance on “generic machinery” for eligibility might complicate arguments for non-obviousness.

Conclusion

The DRP’s decision in Crusoe Energy Systems serves as a reminder that the “directed to” inquiry under Alice Step 1 is not a license to oversimplify claims into their basic purpose. By focusing on the “constituent parts” of the claimed system, the DRP prevented the abstraction of a tangible machine into a mere economic concept. For patent owners, this offers a roadmap for defending eligibility: anchor the claims in physical structure and resist high-level summarizations. For challengers, it signals that the burden to prove ineligibility requires more than identifying a known utility or economic benefit associated with the invention.