Commerce Department Threatens Harvard’s Patents in Unprecedented Bayh-Dole Maneuver

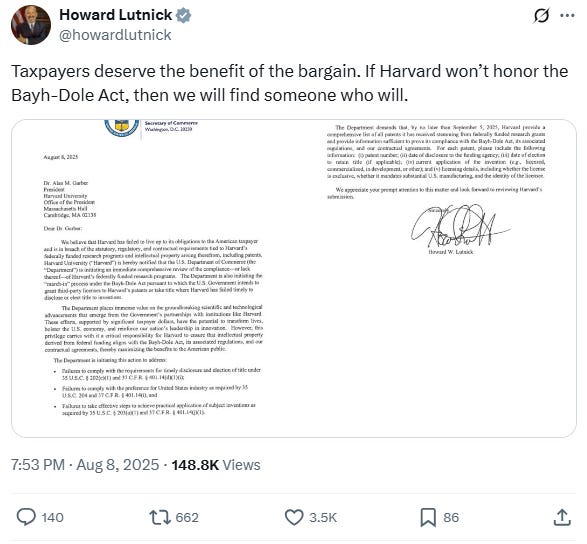

In a move that has sent ripples through the technology transfer community, the U.S. Department of Commerce has initiated a review of Harvard University’s patent portfolio and threatened to exercise "march-in" rights under the Bayh-Dole Act. The action, detailed in an August 8, 2025, letter from Commerce Secretary Howard W. Lutnick to Harvard President Alan M. Garber, represents a significant escalation in both the federal government's oversight of university research and its ongoing dispute with the institution.

For patent attorneys, inventors, and in-house counsel, this development signals a new level of scrutiny for intellectual property derived from federal funding. The letter accuses Harvard of being in "breach of the statutory, regulatory, and contractual requirements tied to Harvard's federally funded research programs and intellectual property arising therefrom" (Letter, ¶ 1).

The unprecedented flexing of this power is a bit alarming. This is not merely a request for information; it is the formal start of a process that could see the government seize title to or grant third-party licenses for some of the university’s most valuable patents.

The Government's Allegations and Demands

The Commerce Department's letter is direct, stating its intention to address what it sees as systemic failures by the university.

Secretary Lutnick wrote that the Department is "initiating the 'march-in' process under the Bayh-Dole Act pursuant to which the U.S. Government intends to grant third-party licenses to Harvard's patents or take title where Harvard has failed timely to disclose or elect title to inventions" (¶ 2).

The Department cites three specific areas of non-compliance (¶ 4):

Failures in the timely disclosure and election of title for inventions.

Violations of the preference for U.S. industry in licensing, as required by 35 U.S.C. § 204.

A failure to take "effective steps to achieve practical application" of inventions.

To that end, the Department has given Harvard a tight deadline of September 5, 2025, to provide a complete list of all patents stemming from federally funded research, along with detailed information on disclosure dates, licensing terms, and commercialization status (¶ 5).

According to a university website cited by Reuters, Harvard held over 5,800 patents as of July 2024, making this a formidable administrative task.

A Historic Threat to a Foundational Law

The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 is a cornerstone of American innovation policy. It allows universities and other non-profit institutions to retain ownership of inventions developed with federal funding, creating a powerful incentive to partner with industry and commercialize research for the public good.

A key enforcement mechanism within the Act is the government’s "march-in right." This provision allows a federal agency to step in if the patent holder is not taking effective steps to commercialize the invention or if other public health or safety needs are not being met. However, the significance of the current situation lies in its novelty. As noted in the Harvard Crimson, "No federal agency has ever exercised march-in rights" since the law's inception.

The letter comes amid a wider, politically charged conflict between the Trump administration and Harvard. The university has characterized the probe as a "retaliatory effort," while the administration’s actions follow disputes over issues ranging from campus antisemitism to federal research funding freezes.

This context suggests the use of Bayh-Dole may be a new form of leverage in a broader political campaign.

Analysis: Benefits, Challenges, and Risks

This action against Harvard presents a complex set of considerations for the entire intellectual property ecosystem.

From the government’s standpoint, a successful enforcement action could reaffirm the core tenets of the Bayh-Dole Act. It would send a serious message to all recipients of federal funding that the obligations for timely disclosure, U.S. manufacturing preference, and practical application are not optional.

For years, public advocates have urged the government to use march-in rights to lower the cost of pharmaceuticals and other products developed with taxpayer money. This action, if pursued, could set a precedent for doing so. Secretary Lutnick’s letter emphasizes the "critical responsibility for Harvard to ensure that intellectual property derived from federal funding... [maximizes] the benefits to the American public" (¶ 3).

For Harvard and other major research institutions, the immediate challenge is compliance. Compiling decades of patent and licensing data under a short deadline is a monumental task.

A greater challenge is the potential loss of control over a lucrative IP portfolio. Technology transfer offices rely on the revenue and industry partnerships generated by licensing to fund further research. The uncertainty created by this probe could disrupt existing and future licensing agreements.

The most profound risk is the potential chilling effect on the U.S. innovation system. The Bayh-Dole Act was created to provide certainty and encourage investment in commercialization. If march-in rights become a tool in political disputes, that certainty evaporates.

Universities may become more risk-averse in pursuing commercialization, and industry partners may hesitate to license technology that could be subject to government seizure. The stability of the technology transfer framework, which has been a powerful engine for economic growth, could be undermined.

Conclusion

The Commerce Department's move against Harvard marks a pivotal moment for the Bayh-Dole Act. Regardless of the outcome—a settlement, a full march-in proceeding, or a retreat by the government—the very threat has altered the relationship between federal agencies and the research institutions they fund.

IP professionals should monitor this situation with close attention. It raises fundamental questions about the balance of power between the government and patent holders, the security of IP derived from federal grants, and the insulation of patent law from political pressure.

For now, the innovation community is left to watch and wait as a foundational law of U.S. technology policy is tested in an unprecedented public showdown.

Disclaimer: This is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or financial advice. To the extent there are any opinions in this article, they are the author’s alone and do not represent the beliefs of his firm or clients. The strategies expressed are purely speculation based on publicly available information. The information expressed is subject to change at any time and should be checked for completeness, accuracy and current applicability. For advice, consult a suitably licensed attorney and/or patent professional.