AI Tools, Patent Bars, and the USPTO's Guidance

Does inputting to a cloud-based tool constitute a public disclosure?

The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) presents both exciting opportunities and significant challenges for patent practitioners. IP attorneys are exploring AI for prior art searches, drafting assistance, file wrapper summaries, and more. Yet, amidst this technological surge, a critical question hangs in the air, largely unaddressed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO): Could using an AI tool inadvertently trigger a public use or disclosure bar, jeopardizing patentability? It’s 2025, the USPTO has commented on AI-based tools on a few occasions, and practitioners still don’t have a definitive answer.

As practitioners know, the bar for what constitutes a "public disclosure" under 35 U.S.C. § 102 is relatively low. The statute states that a patent cannot be granted if "the claimed invention was ... in public use ... or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date." While the pre-AIA focus was on the time of invention, court decisions remain relevant. A public use bar can be created simply by showing or allowing an invention's use by someone "under no limitation, restriction, or obligation of confidentiality" (MPEP 2152.02(c)).

Inventors in the U.S. generally have one year from the date of their own first public disclosure (or a disclosure derived from them) to file a patent application. See MPEP 2153. This grace period is a “shield” for the inventor's own disclosures or disclosures made by others after the inventor has already publicly disclosed the invention. While the grace period offers a safety net for an inventor's own disclosures in the U.S., it is not a universal solution, particularly when considering international patent protection, as most other countries operate under an “absolute novelty” system with no, or very limited, grace periods.

This brings us to AI and cloud-based tools. Consider a drafting attorney inputting detailed descriptions of a novel invention into a generative AI platform. If that input is accessible to anyone else – perhaps system administrators, other users, or even the AI model itself in a way that allows reproduction – and those "others" aren't bound by strict confidentiality, have we crossed the public use threshold? The risk extends to many cloud-based tools, especially those lacking robust security measures and clear confidentiality obligations.

Furthermore, what happens when an AI model learns from the input? If it absorbs those inventive details through retraining and later outputs similar information in response to another user's prompt, could that constitute a public use or even a printed publication down the line? While some argue it's not so clear-cut, the stakes are high, and few seem eager to become the test case.

Confidentiality vs. Public Disclosure: A Nuanced Distinction

Much of the discussion so far has centered on the practitioner's duty of confidentiality. USPTO Rule 11.106(a) mandates that practitioners "shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client" without specific permissions. Consumer-grade AI tools, with their often-vague terms of service and data usage policies, almost certainly fail to meet the rigorous confidentiality standards required.

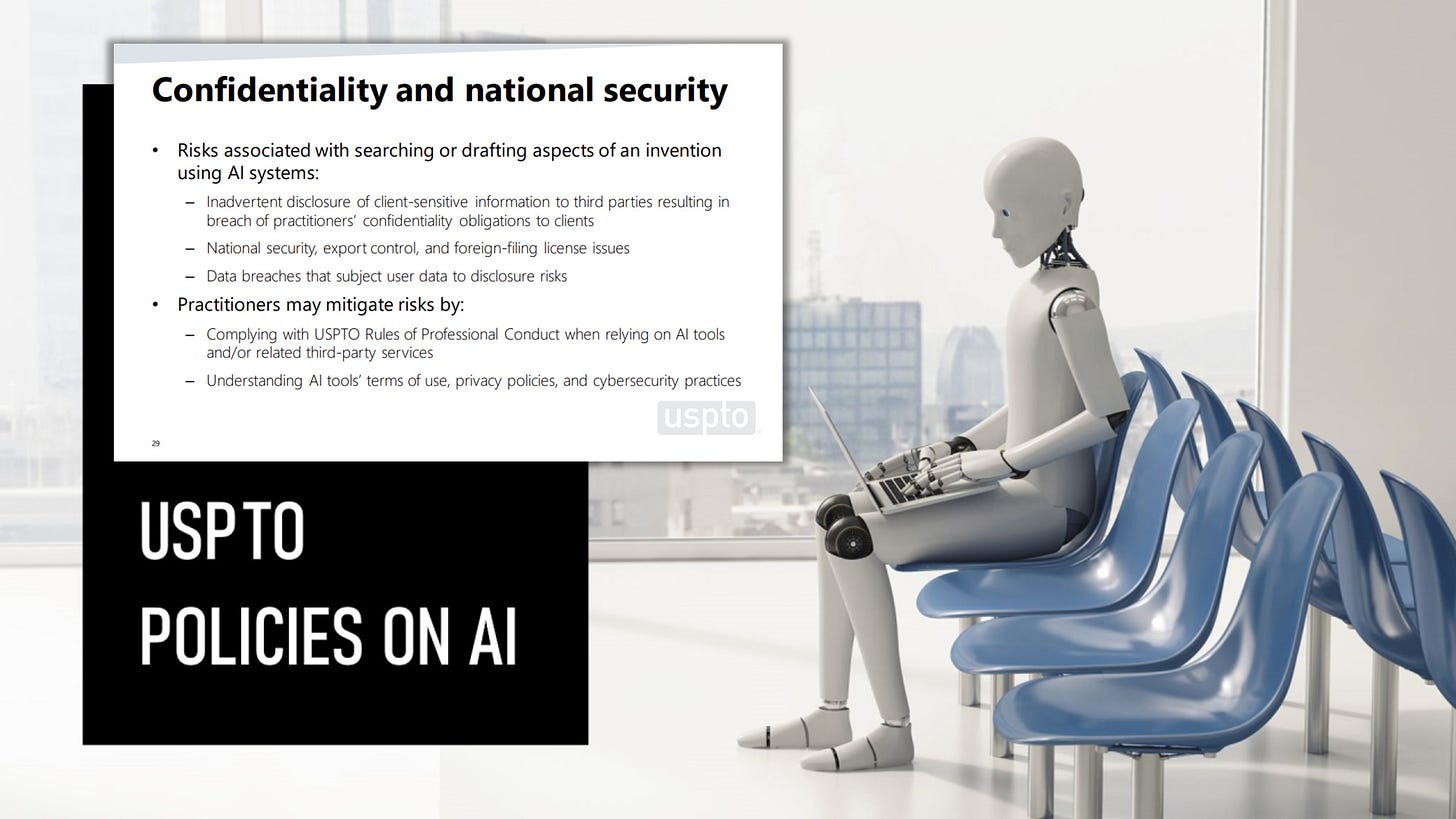

The USPTO itself has touched upon these confidentiality concerns. In May 2024, Nalini Mummalaneni, Senior Legal Advisor, highlighted several key areas:

Duty of Confidentiality: Upholding Rule 11.106 and taking steps to prevent unauthorized disclosure.

Risks of AI Use: Inadvertent disclosure to third parties, including AI owners.

Data Usage Concerns: AI models being trained on sensitive data.

Third-Party Services: Ensuring confidentiality when using external AI tools.

Regulatory Implications: National security, export controls, and foreign filing issues.

Data Security: Understanding terms of use, privacy policies, and cyber risks.

These are all valid and crucial points.

But notice what's missing: a direct discussion of public use and public disclosure bars.

A simple reminder about a practitioner’s duty of confidentiality fails to address the potential stakes: a loss of rights.

The Lingering Question: Why the Silence?

Despite issuing "Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions" (Feb 2024) and "Guidance on Use of Artificial Intelligence-Based Tools" (April 2024), the USPTO has seemingly sidestepped this specific patent-barring question. We are now well over a year past this initial guidance was released, and practitioners are still operating in a grey area.

Is the USPTO's silence an indication that they view this as a non-issue? Is everyone depending on the grace period?

Are policy-makers waiting for a definitive case to emerge from the courts or the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB)? Or are officials simply focusing on the more immediate ethical and procedural concerns, leaving the substantive patent law implications for hindsight?

Navigating the Spectrum of Risk

This uncertainty leaves practitioners in a precarious position. It seems likely there's a spectrum of risk:

Low Risk: Using an air-gapped, private, local AI model where data never leaves the practitioner's secure environment. This should be safe from public use accusations.

High Risk: Inputting sensitive, non-public invention details into a widely accessible, consumer-facing AI tool like the public version of ChatGPT, especially without scrutinizing (or in spite of) its terms.

The crucial question is: Where is the line drawn? Can a sufficiently robust privacy and confidentiality agreement between the AI tool provider and the user, guaranteeing strict confidentiality and limiting access, be enough to prevent triggering a public use bar? Most practitioners would probably like to think so.

Would retaining or retraining with private invention data break confidentiality sufficiently to constitute a public use? Would an AI platform reserving the right for human review of the prompt history for potential abuse trigger a bar? What clauses and prohibitions would such an agreement actually need to contain?

Until the USPTO provides clear guidance or a test case sets a precedent at the District Court and/or Federal Circuit, practitioners must tread carefully.

The allure of AI's efficiency cannot overshadow the fundamental—and potentially fatal—risk of premature public disclosure. For now, extreme caution and a deep understanding of any AI tool’s data handling policies are paramount.

The question remains: Who will be brave (or unlucky) enough to test these waters first?

Disclaimer: This is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or financial advice. To the extent there are any opinions in this article, they are the author’s alone and do not represent the beliefs of his firm or clients. The strategies expressed are purely speculation based on publicly available information. The information expressed is subject to change at any time and should be checked for completeness, accuracy and current applicability. For advice, consult a suitably licensed attorney and/or patent professional.